- Home

- Catherine Raven

Fox and I Page 2

Fox and I Read online

Page 2

The privilege of consorting with a fox cost more than I had already paid. The previous week, while I was in town collecting my groceries, I got a wild hair to stop at the gym. The only person lifting weights was Bill, a scientist whom I had worked with in the park service. I mentioned that a fox “might” be visiting me. “As long as you’re not anthropomorphizing,” he responded. Six words and a wink left me mortified, and I slunk away. Anthropomorphism describes the unacceptable act of humanizing animals, imagining that they have qualities only people should have, and admitting foxes into your social circle. Anyone could get away with humanizing animals they owned—horses, hawks, or even leashed skunks. But for someone like me, teaching natural history, anthropomorphizing wild animals was corny and very uncool.

You don’t need much imagination to see that society has bulldozed a gorge between humans and wild, unboxed animals, and it’s far too wide and deep for anyone who isn’t foolhardy to risk the crossing. As for making yourself unpopular, you might as well show up to a university lecture wearing Christopher Robin shorts and white bobby socks as be accused of anthropomorphism. Only Winnie-the-Pooh would associate with you.

Why suffer such humiliation? Better to stay on your own side of the gorge. As for me, I was bushed from climbing in, crossing over, and climbing out so many times. Sometimes, I wasn’t climbing in and out so much as falling. Was I imagining Fox’s personality? My notion of anthropomorphism kept changing as I spent time with him. At this point, at the beginning of our relationship, I was mostly overcome with curiosity.

I gripped a couple of firm white mushrooms in one hand and reached for one of those slippery plastic sacks with the other. The Timex face flashed on my exposed inner wrist. Forty-five minutes shy of 4:15 p.m. The fox! Meeting a fox that I wanted to jettison suddenly felt more important than mushrooms for which I was driving sixty miles round trip. I shook the bag several times, but it refused to open, so I jammed the mushrooms back onto the shelf between some oranges and pushed my full cart to the registers. While calculating the time needed to drive home through a gauntlet of white-tailed deer along a two-lane road, I somehow ended up in the empty express-checkout lane. A cowboy rolled in behind me. The clerk observed my cart, raised her eyebrows, smiled, and said nothing. She was supposed to ask if I had found everything I was looking for; she wanted to ask if I could count to eight.

“Yes. Thank you,” I answered the unasked question, “but I regret abandoning some mushrooms at the last minute.”

Her eyebrows dropped. Eyes rolled.

I pulled a wallet out of my back pocket. “Shame about the mushrooms,” I said, flipping through the cash. Then I turned to the cowboy and noticed he was about 110 years old.

“Goodness. Just a little bunch of bananas.” I bent over his cart and peered inside. Nothing. Just bananas. “Didn’t even need a cart for that, did you?”

“Needed something to hold me up,” he said, “while waiting.”

For a moment I considered the remark, wondering if it had some underlying message. The cue hadn’t been in the cowboy’s words, but in his flinty-eyed stare. He’d expected an apology. Halfway home, I realized that he was annoyed that I was in the wrong checkout lane. I hated missing social cues. For every cue I caught too late, I worried about another few flying right over my head.

But more so, I worried about not being home when the fox came visiting. He was an uninvited guest and I couldn’t keep him waiting. Uninvited guests are quite unlike invited guests, whose entitlement (I imagine) allows them to overlook their host’s temporary tardiness. Invited guests will call, “Yoo-hoo!” and without waiting to see if “yoo” is even home, they will let themselves in. They will saunter over to the fridge and grab a drink. But uninvited guests are fragile, and you need to greet them punctually to minimize the discomfort inherent in their ambiguous status. Most problematic is the uninvited guest who knows he’s expected.

Unless I was home in forty minutes, a red fox would trot his reasonable expectation of hospitality down to my cottage, scratch the dirt, sniff the air, feign preoccupation, and expend his tiny reserves of patience and humility. Then he would slip away in a dreadful sulk. This could not be explained to a 110-year-old cowboy propped up by a five-banana cart, but it was true nonetheless.

Motoring down the driveway, I scanned the chubby hill across the draw. A vertical cliff with a sassy tilt to the north lay on top of the hill like an elegant pillbox hat. In the middle of the cliff, on a ledge tucked into a shaded pleat, a golden eagle rose from its nest. I ran upstairs, leaned onto the window ledge, and searched for the fox. When the tip of his tail breached the wheatgrasses, I led him with binoculars as though he were a grouse ahead of my 20-gauge. Leading, a traditional hunting skill, requires hunters to anticipate an animal’s speed and direction, keeping the barrel, sights, or scope just ahead of the moving target. Fox was an easy lead. His tail bobbed brazenly down the fall line. My college textbook claimed that wild animals instinctively elude their natural enemies. That may be true for a generic fox, but this specific fox was not eluding the golden eagle; he was bounding down the hill to the tune of the “William Tell Overture.”

As the golden eagle rose from its nest, a hundred feet below it a tiny dog fox was journeying down the draw. Just as the fox reached a blue-roofed house, the garage door roared shut and he turned sharply to run along the only clear path to the river, a dirt road adjacent to a rivulet lined with cottonwoods. An alfalfa field as green and neat as a pheasant’s neckband stretched along one side of the rivulet. Dry hummocks as mottled and messy as a pheasant’s tail pushed against the other side.

Across the river, fields bounced into hills, hills rose into forests, forests slid off steep cliffs, cliffs tucked underneath snowcaps. Beyond the snowcaps, rows of mountain ridges stretched endlessly. Where the mountains ended, or if they ended at all, the eagle could not know. After watching the fox disappear into the thick leafless willows along the river’s edge, the eagle flew upriver, where newborn lambs dotted the nearby fields.

The fox crept under the shrubs until his front paws dipped into the river. He stared at a newly exposed sand island glowing in the sun. The fox could swim, but he preferred not to. In any case, the river, almost at high water, was muddy and tumbling wide, drowning last autumn’s braided channels, spits, and gravel shoals. Not even a moose would try to cross. And today? Today a girl might be waiting for him.

Later, the eagle saw two animals outside the blue-roofed house: a fox moving west toward the sagebrush hills, and a person heading east toward the river. Quartering lower, the eagle decided they were not going in separate directions; they were walking—the two animals—toward each other.

I left The Little Prince and an iced tea next to my camp chair and went looking for Fox. I spotted him trotting back from the river, following a trail that swung below my cottage. He could have either stayed the course and avoided me altogether or broken trail and marched uphill to meet me at the rendezvous site. I walked directly toward him, tripping over pits and mounds where the skunks had been digging, stubbing my toes on mud-mired rocks the size of melons, fighting through thigh-high pea thickets. Clover vines clawed at my burr-covered shoelaces. When he was about nine meters away, he stopped and watched me. Had I wandered around obstacles instead of through them, turned my gaze toward the singing meadowlark, or stooped to pull a weed, he would not have understood that I was expecting him. Standing at the meadow’s edge, I wrapped my arms around my chest and squatted like a frog, tucking my torso between my knees. He saw me waiting and started for his regular spot next to the forget-me-not. I followed.

I continued reading out loud from where we’d left off the day before. After two paragraphs, I held up the open book and showed him a prince with hair as blond and spiky as an antelope fawn. Switching from reading to summarizing, I continued, “The little prince lives on an asteroid—it’s a miniature planet. The planet has one flower—a rose. She’s vain. Her petals . . .” I p

laned a hand like a 737 on takeoff (just for emphasis), “flat. Like a face-lift. Never wrinkled. Yeah, I know, Fox.” I nodded. “But the prince loves the rose.” My throat, prone to laryngitis, tightened against the hot, dry wind.

Like all domestic roses, the prince’s rose was high-maintenance. “Here she is, swollen with water”—I held up an imaginary beach ball—“sending . . . demanding that the prince fetch more water.” I tossed the beach ball over Fox’s head and reached for the glass of iced tea sweating next to me. Fox’s eyes followed the glass. He twitched and startled; I set the tea down without drinking. “He polished her single thorn just to appease her vanity.”

Fox winked and stared intermittently. I coughed without looking away from him, silently counted to fifteen, including the “one thousand” pauses in the middle, coughed again. “I know what you are thinking, Fox. The rose is not in love with the prince. He is wasting his time.”

Fox sat up and cocked his head in the classic pose of canine inquisitiveness. This encouraged me to continue summarizing. I pointed to the single-flowered forget-me-not and explained that a rose, like the forget-me-not, is a plant: a small, sessile autotroph with a short life span and limited emotive capabilities.

“This obviates the question about whether the rose is really in love, Fox.”

I paused and counted. He showed no sign that he had found that last comment flippant, so I continued recapping the plot. “The prince propels off his planet, travels all over the universe, and ends up on Earth. He wanders through the Sahara.” I told Fox that the prince stumbles upon the delusional Saint-Exupéry, who is trying to patch a broken airplane and a relationship with a woman he’s left behind. “The woman, like the rose, is spoiled and vain.”

At the time I was reading to Fox, there were fifty million copies of The Little Prince in circulation. You could read it in 160 languages. The book’s author, Antoine Saint-Exupéry, a pioneer in the field of aviation, had written the international bestselling novella Night Flight, winner of the Prix Femina, and Wind, Sand and Stars, a memoir that the National Geographic Society considered the world’s third best adventure book. During Saint-Ex’s heyday—the 1930s and ’40s—the world’s rich and cultured elite rolled out their welcome mats for him.

But he preferred places where he was not welcome. The Sahara, for example. Saint-Ex could do without civilization and maintained a desultory relationship with it all his life. Despite having access to the world’s most sophisticated people, he preferred talking to baobab trees, roses, foxes, and God.

You mean he talked to himself?

No. I mean he talked to baobab trees, roses, foxes, and God. I imagine he also talked to himself. He socialized with people, plants, and wild animals who were unashamed or unaware of their eccentric appearance: lopsided haircuts, wilted leaves, rumpled trousers, mouse tails stuck on their upper lips. Saint-Ex didn’t care about social facades. He liked being around people who imagined widely and with a hint of magic—like a child. And so he wrote a book in which he vets potential companions by showing them a copy of a child’s drawing, a beast in situ, and asking them to identify it. Everyone quickly and confidently identifies the beast—as a hat.

The “hat” turns out to be a boa constrictor digesting an elephant. Only the little prince correctly identifies the drawing, and he’s an extraterrestrial. In other words, Saint-Ex—French war hero and fearless explorer of the Sahara—had imaginary friends.

In 1935, Saint-Ex’s single-engine plane exploded over the Sahara. He leapt from the cockpit to safety. Able to walk, but without communication, food, or water, he became a self-described “prisoner of the sand.” When death became imminent, he occupied himself by observing the survival strategies of animals. He interpreted the activities of foxes—when they hunted, ate, and paired—from their signs. Eventually, he found their den. He could save himself if he killed a fox and drank its blood. He didn’t. Instead, he thanked the foxes for their friendship in his dying hours.

Eventually rescued by nomads, Saint-Ex survived the desert but not the Second World War; his P-38 Lockheed Lightning reconnaissance plane crashed into the Mediterranean Sea in 1944.

After hunting, the fox stretched himself into a long thin line on the gravel driveway, stomach down, shoulders and both front legs stretched back toward his hips, pads up. The wind licked his gray fur cross—one streak down his back and one the length of his shoulders—into calico. When he finished sunbathing, we hiked to his den. Despite the presence of a well-worn route, he gerrymandered the trail to avoid facing the sun. He was already inside the den when I said goodbye. I told him I was off to teach a wildlife class in Yellowstone and would return in half a fortnight.

The next day, I arrived at class hoarse. “Talking the ears off a visitor,” I told the students. Luckily, no one asked if my visitor had talked back, because Fox, the runt of his litter, had been born mute. When he opened his mouth, only one faint sound escaped—qwah—like the last gasp of a dying duck.

Our field campus, built as a vacation resort, was comprised of a semicircle of shiny, varnished log cabins stuck together two by two, each pair surrounded by freshly mowed lawn. A lodge with a great high ceiling and windows all around served as our auditorium and dining hall. Separating the lawn from the river was a cobblestone beach, where carnelian-stemmed coyote willows waved with the slightest breeze. Outside the cabins: long wooden decks. Inside: rough-hewn pine furniture, wildlife-patterned upholstery, TV sets, and thirty-two students looking to augment their knowledge of natural history.

After dinner, I showed slides and told stories about wildlife, starting with the three species we could see from the cabins: pronghorn antelope, Rocky Mountain elk, and bison. In the first story, an antelope harem is placidly feeding in a tight group when one doe makes a lightning-fast run for freedom. The dominant buck chases down the escapee, rounds her off, and trots her back to his harem. Almost immediately, a second doe charges for the hinterlands. The buck responds as with the first. While the second runaway resumes feeding, a third female flees. I showed a slide of a panting buck facing the camera. I interpreted his look as “total exasperation” and heard stifled laughing. I moved on to elk without pausing.

With their heads upright, a group of cow elk are sitting with their butts together. When photographed from the hillside above, they look like spokes on a wagon wheel. On another hillside in deep snow, two bull elk sit tail to tail, rotating their heads to enjoy 360-degree vigilance in an area dense with wolves. In the next slide, wolf tracks surround a bloody bull carcass. “Males are more likely than females to be killed by wolves. In fact, even where there aren’t wolves around, bulls don’t live as long as cows. Why?” Students stir. I shake my head. “No. Don’t even try that joke. I’ve heard it so many times: Why do men die before their wives?” I pause before the hackneyed punch line, “Because they want to.” I tell them that cows live longer than bulls because they are mammals. Among mammals, the gender responsible for child-rearing lives longest. I return to the pair of bulls. In the next slide, one of them has shirked his responsibility. Instead of being on the lookout for wolves, he has placed his head in the snow and fallen asleep. “Males engage in activities,” I tell them, “that are not evolutionarily stable.” They laugh at my interpretation because they think I’m talking about people. Tomorrow we’ll watch a biker without a helmet cross a double yellow, pass an RV around a blind curve, and edge his Kawasaki along a 300-foot cliff face. Following what sounds like a collective gasp, I’ll hear “not evolutionarily stable” recited by a chorus of voices.

The last in the series of bison stories starts with a herdlet meandering around thinly frozen ponds. One adult cow falls through the ice and descends into freezing water. She buoys herself up, dog-paddles to where she fell in, secures both front legs on the snowy edge of the hole, and, with her backbone twisting like a black python, she strains to pull herself over the lip. She almost makes it. Exhaling loudly, she slips backward. Another adult c

ow stands sentinel at the hole’s slippery edge, watching for three hours until the drowning cow finally sinks. I ask the class whether the sentinel cow is loyal or stupid.

I lecture while the students shuffle and scribble, point while they lean and whisper, pause while they cough and sneeze. Each time, after asking a question, I count to fifteen. For most of my life, except for these sporadic lectures, I spoke in soliloquy or not at all.

Uncomfortable with dialogue—let alone group conversations—I blocked out the extemporaneous noise filling the auditorium. Instead, I listened to the inherent rhythm of the sounds around me: the stories I told, spoken slowly and steadily with intermission for questions, and the fast, jerky speech in response. No one answered my question about the sentinel bison, but I considered the talk a success anyway, since I remembered not to use words like fortnight.

“I am an a cappella singer,” I told the fox when I got home, “and I have been trapped in a jazz band.”

After the presentation, a student walked me back to my cabin and asked about my pets.

I didn’t grow up in a house with pets. Since leaving college I’d been too transient, and I’d been taking jobs like this one, which had me sleeping in a different bed so many nights of each month. And now that I was spending time with Fox, I couldn’t imagine that I would ever be willing to own an animal.

“No pets,” I said, shaking my head until I realized that she’d think I was abnormal and then I’d have to explain myself. “Not now,” I added when we stopped at my cabin door.

“That’s funny about not having a pet.”

Fussing with the stubborn door lock kept me from making eye contact. “Really? Funny?”

“There were a few animal slides . . . ,” she said, turning to walk to her cabin in the dark. “I was sure you were going to call the little fellow ‘Foxie.’”

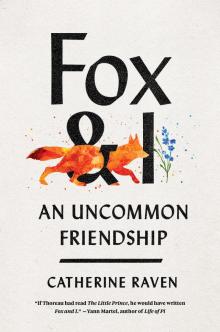

Fox and I

Fox and I